2026 North Atlantic right whale calving season

2026 North Atlantic right whale calving season

With only around 380 North Atlantic right whales remaining in the ocean, every individual matters for the survival of this critically endangered species. That’s why every year, in the southeastern US, we track the births of new North Atlantic right whale calves.

Sadly, North Atlantic right whales face threats in the form of vessel strikes, entanglement in fishing gear, ocean noise pollution, and climate change. They can live up to 70 years, but increasing fishing and boating activities—not to mention the imminent threat climate change poses to ocean temperatures—shorten the lifespans of these magnificent marine mammals, who are some of the largest living animals on Earth.

North Atlantic right whales are not reproducing fast enough to offset their deaths. Since NOAA declared an Unusual Mortality Event in 2017, there have been 41 documented right whale deaths, 40 serious injuries and 87 morbidities, which represents over 40% of the current North Atlantic right whale population. Further, research suggests that that only 1/3 of right whale deaths are documented, so the death toll is likely much higher. In comparison, there have only been 100 births in this same period—and at least nine of those calves died in the same season they were born.

The North Atlantic right whale calving season begins each year in mid-November and ends around mid-April. With only 70 reproductive female North Atlantic right whales remaining, we keep a close watch on them and their new calves to help ensure their survival. Considering these current numbers, 20 new calf births would be considered a relatively productive calving season. However, given the high rate of mortality and injury, North Atlantic right whales need to have at least 50 new calves per year to recover and grow their population. If the species fell to only 50 reproductive females, they would become functionally extinct.

To stay up to date with the latest 2026 North Atlantic Right Whale Calving Season news and receive updates about the births of new whale calves, bookmark this page and check back in regularly. You can also follow us on Instagram, Facebook, and TikTok for live updates.

(#1 ) 28 November 2025 — Champagne spotted with her second calf

The first mom-calf pair of the 2025–2026 season has been sighted off South Carolina. Champagne (#3904), a 17-year-old female, was spotted by Clearwater Marine Aquarium’s aerial survey team with her second known calf. Born in 2009 to Spindle (#1204)—the most prolific mother in the known population—Champagne is part of a large and complex family tree. Her first calf, Wall-E, was born in 2021, making this five-year calving interval a hopeful sign for right whale recovery.

Despite enduring five entanglements herself, and 21 across her immediate family, Champagne shows remarkable resilience. She carries visible scarring but continues to thrive. This new calf represents not just another birth, but a testament to endurance in the face of human threats.

(#2) 3 December 2025 — Millipede welcomes her third calf

Florida Fish and Wildlife spotted the season’s second mom-calf pair off the Florida–Georgia border: 21-year-old Millipede (#3520) with her third known calf. Born in 2005 to Naevus (#2040) and part of a vast family tree tracing back to matriarch Wart (#1140), Millipede represents a strong maternal line. Her own calves include one born in 2013 and another in 2021.

Millipede has survived four entanglements and a vessel strike. Her name comes from a series of healed propeller scars—evidence of a boat collision when she was just a year old. Tragically, her family has suffered greatly from similar encounters, with at least three relatives killed by vessels. Each new calf is a chance to carry forward resilience, and a reminder of the threats these whales still face.

(#3) 4 December 2025 — Callosity Back becomes a first-time mom

Spotted off South Carolina by Clearwater Marine Aquarium’s team, Callosity Back (#3760) has been seen with her very first calf—making her the first-known new mother of the 2025–2026 season. Born in 2007 to Derecha (#2360) and Gemini (#1150), Callosity Back is the first of her mother’s offspring to calve, making Derecha a grandmother for the first time.

She’s easily recognizable thanks to a rare callosity patch on her back—a feature typically only seen on right whales’ heads. Despite three known entanglements early in life, she has remained free of further incidents for over a decade. With a family history that includes 28 entanglements and one vessel strike, every new calf is both a celebration and a reminder of what’s at stake.

(#4) 10 December 2025 — Bocce spotted with her second known calf

Clearwater Marine Aquarium’s Georgia team spotted Bocce (#3860) with a new calf off the coast of Georgia, marking the fourth mother-calf pair of the 2025–2026 season. Born in 2008 to Naevus (#2040) and Trident (#1113), Bocce is part of a prolific family tree—including her sister Millipede, also a mother this year.

This is Bocce’s second cataloged calf, though she may have given birth more than once before. In 2016, she was seen nursing a calf later confirmed to belong to another mother, following a rare three-way calf swap. Her naming comes from the scattered circular callosities on her head, resembling a bocce ball setup.

Despite enduring three entanglements and two vessel strikes, Bocce has survived with only minor injuries. With 31 entanglements and two vessel strikes recorded across her immediate family, her resilience is remarkable—and vital as this newest calf begins life in challenging waters.

(#5) 11 December 2025 — Squilla returns with her second known calf

The fifth calf of the season was seen off South Carolina by Clearwater Marine Aquarium’s team. Squilla (#3720), a 19-year-old female, was spotted with her second known calf. Born to Mantis (#1620), Squilla’s name reflects her mother’s influence—derived from Squilla, the genus of the mantis shrimp, and a nod to the distinctive callosity patterns on her head.

Squilla has survived three entanglements with minor injuries, but her family’s story underscores the harsh reality right whales face. Her first calf (#5120) died at just three years old after two years entangled in fishing gear. Her niece and nephew also died from entanglements at young ages—tragic losses that highlight how especially deadly these threats are to growing whales.

With each new calf, the species gets a little more hope. Let’s hope this one brings a new chapter to Squilla’s family story.

(#6) 16 December 2025 — Cascade spotted with her fourth known calf

Clearwater Marine Aquarium’s Georgia team has confirmed the sixth mom-calf pair of the season: Cascade (#3157) and her newest calf, seen off the coast of Georgia. Born in 2001 to Moon (#1157), Cascade is now a 25-year-old mother of four. Her name comes from the white scarring that “cascades” down either side of her head—a visual reminder of the threats right whales carry on their bodies.

Cascade’s family has endured more than its share of hardship, with 36 recorded entanglements and one vessel strike across her parents, siblings, and offspring. Her first calf, FDR (#4057), hasn’t been seen since suffering a severe entanglement in 2016. Thankfully, Cascade’s two most recent calves are still observed regularly, and her own entanglements—while visible—have not impacted her reproductive health.

Each calf born to an experienced, resilient mother like Cascade is a critical win for the survival of this species.

(#7) 17 December 2025 — Harmonia sighted with her fourth known calf

The seventh mom-calf pair of the season was confirmed off Georgia by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources and Clearwater Marine Aquarium teams. Harmonia (#3101), a 25-year-old female, was seen with her fourth known calf. Born to Aphrodite (#1701) and Velcro (#1306), Harmonia’s name—and those of several relatives—draws from Greek mythology, a literal tribute to her lineage.

Harmonia holds a grim record: with ten known entanglement events, she is the most entangled right whale in the catalog. Yet despite this, she has now given birth to four calves—a testament to her extraordinary resilience. Sadly, two of her previous calves are presumed dead due to vessel strike and entanglement, and her third, Agave (#5001), has already been entangled multiple times.

Her new calf brings another chance—for the continuation of one whale family and the recovery of this vital population.

(#8) 20 December 2025 — Tripelago spotted with her sixth known calf

The eighth calf of the 2025–2026 season was confirmed off the coast of Georgia by Clearwater Marine Aquarium Research Institute’s South Carolina aerial survey team. Tripelago (#2614), a 30-year-old North Atlantic right whale, was seen with her sixth known calf near Ossabaw Island. As one of the more experienced mothers in the population, each successful birth adds valuable momentum to the species’ recovery.

(#9) 21 December 2025 — Echo spotted with her fourth known calf

Clearwater Marine Aquarium’s Georgia team has confirmed the ninth mom-calf pair of the season: Echo (#2642), a 30-year-old female, and her newest calf. Born in 1996 to Kleenex (#1142) and Dingle (#1144), Echo is now a mother of four—her previous three calves are all still seen regularly.

Echo’s name comes from the single circular callosity on her head, reminiscent of a Morse code “E”, or “echo” in the NATO phonetic alphabet. Her family history spans generations, with 10 siblings and 20+ descendants, but it’s also marked by frequent harm. Her mother, Kleenex, was last seen entangled in 2018 after at least four years of carrying rope around her head. Echo herself survived a vessel strike as a calf, leaving a permanent injury to her fluke, and endured a severe entanglement just two years ago in 2023.

That she is here today—with a new calf by her side—is remarkable. Every healthy mother-calf pair is a hopeful step toward recovery for this critically endangered species.

(#10) 23 December 2025 — Bermuda sighted with a new calf

The tenth North Atlantic right whale calf of the season was seen off Amelia Island, Florida, by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission aerial survey team. Bermuda (#3780) was spotted with her calf—another vital addition to this critically endangered population.

(#11) 23 December 2025 — Uca spotted with her calf off South Carolina

The eleventh calf of the 2025–2026 season was confirmed by Clearwater Marine Aquarium Research Institute’s aerial survey team. Uca (#3390) was seen with her calf east of Saint Phillips Island, South Carolina—another promising sign in a season already showing signs of cautious hope.

(#12) 26 December 2025 — Mantis seen with her eighth known calf

Photographed east of Kiawah Island, South Carolina, Mantis (#1620) was spotted with her eighth known calf—the twelfth confirmed mother-calf pair of the 2025–2026 calving season. As an experienced mother, Mantis continues to contribute significantly to the recovery of the North Atlantic right whale population. Her long reproductive history makes each new calf she births all the more impactful.

(#13 and #14) 27 December 2025 — Two more moms spotted: Juno and Binary

On the same day, two new right whale mom-calf pairs were confirmed off the coast of Georgia, bringing the season total to 14. Juno (#1612) was seen east of Wassaw Island with her ninth known calf, and Binary (#3010) was spotted with her fourth known calf east of Blackbeard Island.

Juno and Mantis are estimated to be over 40 years old—among the oldest known females in the population. Juno’s legacy includes nine calves, with two breeding daughters still contributing to the survival of her lineage. Binary, now over 26, has also made a meaningful contribution with two living sons and a female offspring not seen since 2012.

These sightings are a reminder of the vital role that experienced mothers play in sustaining this critically endangered species.

(#15) 1 January 2026 — Boomerang begins the new year with calf #5

On New Year’s Day, the fifteenth North Atlantic right whale calf of the season was sighted east of the St. Mary's River, near the Georgia–Florida border. Boomerang (#2503), a 31-year-old female, was observed with her fifth known calf by Clearwater Marine Aquarium Research Institute’s aerial survey team.

As an experienced mother, Boomerang continues to play an important role in the survival of this endangered species—each calf a new reason for hope.

(#16) 5 January 2026 — Skittle seen with a new calf

The sixteenth mom-calf pair of the season was spotted by Florida Fish and Wildlife’s aerial survey team: Skittle (#3260) and her third known calf. First sighted in 2002, Skittle is at least 24 years old. Her name comes from the bowling pin-shaped callosity pattern on her head—“skittle” being the historic term for the pin.

While Skittle has had two previous calves, neither survived beyond their first few weeks. She was seen with calves in both 2010 and 2024, but each time was later resighted alone on the calving grounds—an uncommon but heartbreaking trend. Calves are entirely dependent on their mothers for milk during their first months, and separation at that stage is fatal.

This calf marks a fresh chance for Skittle, and a hopeful turning point in her story.

(#17) 6 January 2026 — A rare sighting: Catalog #3593 returns with a calf

The sixteenth North Atlantic right whale calf of the season was spotted by Florida Fish and Wildlife’s aerial survey team, alongside its mother, Catalog #3593. First seen in 2005 as what appeared to be a full-grown adult, this elusive whale remained a mystery until she was documented with her first calf in 2021. That calf, now Catalog #5193, has since been seen regularly—but until now, #3593 hadn’t been seen again.

In over two decades, she has only been sighted nine times across five different years, with no records of her visiting major right whale habitats like Cape Cod Bay or the Gulf of St. Lawrence. While her movements remain unknown, one thing is clear: each time she resurfaces with a healthy calf, it’s a welcome surprise for the species.

(#18) 8 January 2026 — Young and thriving: Catalog #4610 welcomes her first calf

The eighteenth North Atlantic right whale calf of the season was spotted off West Onslow Beach, North Carolina, by Clearwater Marine Aquarium’s aerial survey team. Catalog #4610, born in 2016 to Swerve (#1810), is just 10 years old—making her both the youngest mom and only the second first-time mom of the 2025–2026 calving season.

With four siblings and two nieces and nephews in the catalog, she represents a growing and active maternal line. Remarkably, Catalog #4610 has no documented injuries from entanglements or vessel strikes—an increasingly rare status for this species. In recent years, first-time mothers have typically been older, often between 15 and 20 years of age. Her early calving may point to the potential for healthier, more natural reproductive timelines when whales remain free from human harm.

(#19) 16 January 2026 — Magic spotted with her eighth known calf

The nineteenth North Atlantic right whale calf of the season was sighted off Amelia Island, Florida, by Clearwater Marine Aquarium’s aerial survey team. Magic (#1243), now 44 years old, is among the most experienced mothers in the population—this marks her eighth known calf.

Born in 1982 to Catalog #1242 and Orangepeel (#1617), Magic’s family tree is long but marked by tragedy. Her sister Reyna (#1909) was killed by a vessel strike while pregnant, and her first calf, Lucky (#2143), survived a serious propeller strike as a baby—only to die later during her first pregnancy when the injury reopened.

Magic herself has survived two entanglements and continues to defy the odds. She’s now one of six moms this season who last calved in 2021, and her return is a powerful reminder of what’s possible when these whales survive long enough to keep contributing to the species' future.

(#20) 20 January 2026 — Giza and calf spotted thanks to alert boaters

The twentieth North Atlantic right whale calf of the season was reported by recreational boaters off the South Carolina coast, who shared footage of a right whale pair to NOAA’s sighting hotline. The whales were confirmed as Giza (#3020) and her fourth known calf.

Giza was first seen in 2000 at an unknown age, making her at least 26 years old. She’s named for the Egyptian pyramids, as three distinct features on her callosity pattern mirror their alignment. Her previous cataloged calves—Hopscotch (#3820) and Brussels Sprouts (#5191)—were also named for the shapes of their callosities. In 2024, Giza reached a new milestone when Hopscotch became a mother, making Giza a grandmother.

Giza and both of her named calves have survived minor entanglements, a reminder of the persistent risks these whales face. Thankfully, this latest calf brings new life to a growing and resilient family line.

(#21) 22 January 2026 — Slalom sighted with her seventh known calf

The twenty-first North Atlantic right whale calf of the season was spotted just off Daytona Beach, Florida, by beachgoers—later confirmed to be Slalom (#1245) and her newest calf. Born in 1982 to Wart (#1140), Slalom is now 44 years old and a mother of seven. Her distinctive callosity pattern, full of bumps and turns, earned her the name “Slalom,” like the winding course of a ski slope.

As the eldest daughter of the prolific Wart, Slalom is part of one of the most expansive family trees in the catalog. Her nieces Millipede and Bocce are also raising calves this season, making it a strong year for her lineage. But that size comes with a cost—Slalom has survived seven entanglements, with visible scarring on her head and tail, and her immediate family has endured dozens more entanglements and multiple vessel strikes.

Despite these challenges, Slalom continues to bring new life into the population, reinforcing the importance of protecting long-lived, reproductive females.

(#22) 30 January 2026 — Ghost reappears with her ninth known calf

The twenty-second calf of the season was spotted off Flagler Beach, Florida, by beachgoers and confirmed by the Marineland Right Whale Project. Ghost (#1515), first identified in 1985 with a calf, is now estimated to be at least 50 years old—possibly older—making her one of the oldest known right whales actively calving.

This marks Ghost’s ninth known calf. Four of her calves weren’t cataloged, likely due to limited sightings or insufficient documentation during their early years. With expanded survey coverage in recent decades, most calves can now be tracked throughout their lives, making Ghost’s ability to keep contributing all the more meaningful.

Named for the ghost-like shape of the callosity pattern on her head, Ghost has only experienced one minor entanglement during her long life. Of her four cataloged calves, three are still seen regularly, with only a handful of minor incidents among them. Her story is a rare one of longevity, resilience, and continued hope for the species.

The North Atlantic Right Whale Catalog keeps track of every whale and whale calf identified by researchers. Every whale is assigned a four-digit number, but many are also given names—especially those that have unique physical features or interesting stories.

11 new calves were born last year during the 2025 season. You can learn more on IFAW’s 2025 calving season report card.

In the year prior (2024), researchers identified 20 new calves, but sadly five died or are presumed to be dead.

Here’s how many right whale calves have been born since the 2007 season:

- 2025: 11 calves

- 2024: 20 calves

- 2023: 12 calves

- 2022: 15 calves

- 2021: 20 calves

- 2020: 10 calves

- 2019: 7 calves

- 2018: 0 calves

- 2017: 5 calves

- 2016: 14 calves

- 2015: 17 calves

- 2014: 11 calves

- 2013: 20 calves

- 2012: 7 calves

- 2011: 22 calves

- 2010: 19 calves

- 2009: 39 calves

- 2008: 23 calves

- 2007: 23 calves

Between the years of 2007 and 2022, 15.7 calves were born on average each season. Since the Unusual Mortality Event that was declared in 2017, only 11 calves have been born on average each season.

How reproduction works for right whales

Every year, North Atlantic right whales migrate more than 1,000 miles from their northern feeding grounds to the shallow, coastal waters in the southeastern US. This is where they breed and birth their calves.

Potential mothers are at reproductive risk due to escalating stressors in the environment. Research shows that the energetic impacts of sub-lethal entanglements and other stressors are stunting the growth of whales; shorter body lengths are associated with longer birth intervals and low birth rates.

Females that have severe injuries from entanglement have the lowest birth rates. As the health of female right whales declines, their birthing intervals increase.

How many babies do North Atlantic right whales have?

The gestation period for North Atlantic right whales is about one year long. After their year-long pregnancy, the mother gives birth to a single calf. Female North Atlantic right whales typically become sexually mature at 10 years old.

The calving interval for reproductive females is widening. Adult females previously gave birth to a calf every three years, but now they are only calving every six to 10 years, likely due to the additional stress of entanglement, climate change, and other threats.

How long do North Atlantic right whale calves stay with their mothers?

North Atlantic right whale calves are typically weaned at about one year old.

How big are North Atlantic right whale calves?

Newborn North Atlantic right whale calves are about 13 to 15 feet long and weigh about 2,000 pounds. As adults, they grow to 45 to 55 feet long and can weigh up to 70 tons.

How do we keep track of each individual North Atlantic right whale?

Individual whales are easily identified by callosities, which are raised patches of white roughened skin on their heads, and other distinct scars. North Atlantic right whales are the only whale species that has callosities. Each individual has a distinct pattern of callosities. Callosities appear white because these whales have cyamids, commonly known as whale lice, which are a type of skeleton shrimp parasite.

How do North Atlantic right whales socialize?

Right whales can be observed actively socializing at the ocean’s surface. Whales doing so are known as surface-active groups (SAGs). Their mating occurs in these SAGs. They communicate with each other using low-frequency groans and pulses, which is why ocean noise pollution has such a negative impact on whales.

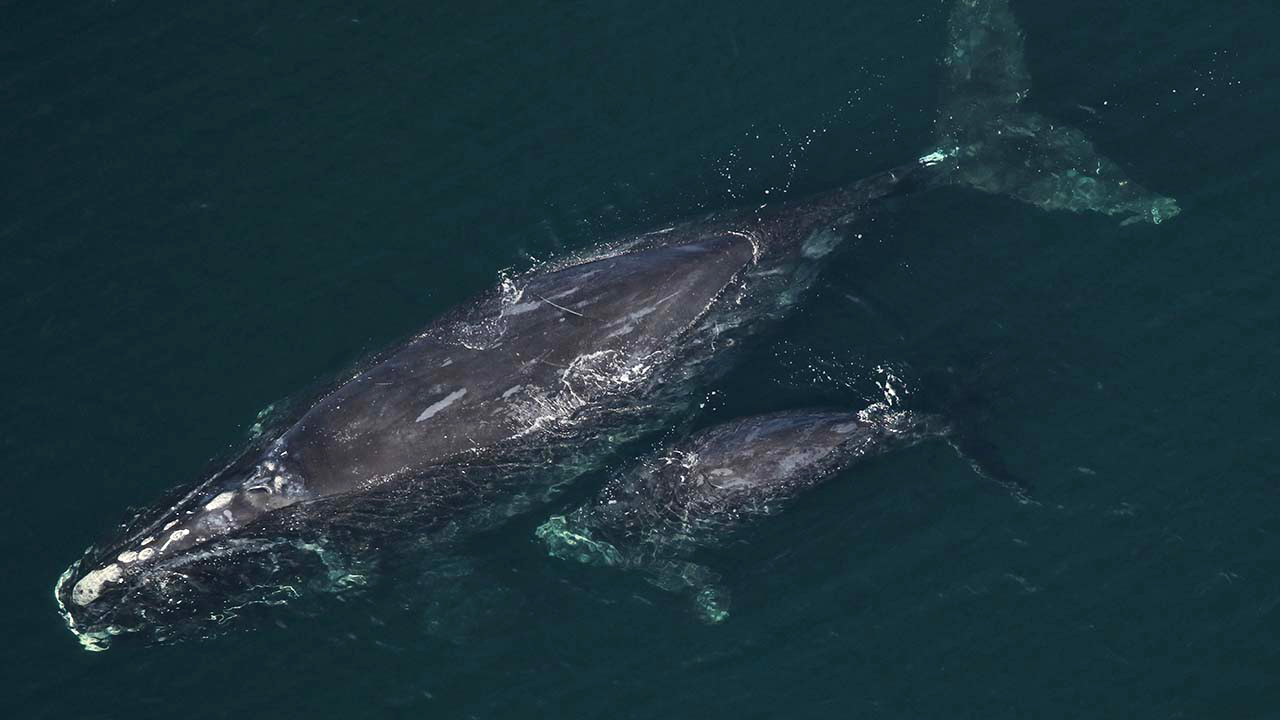

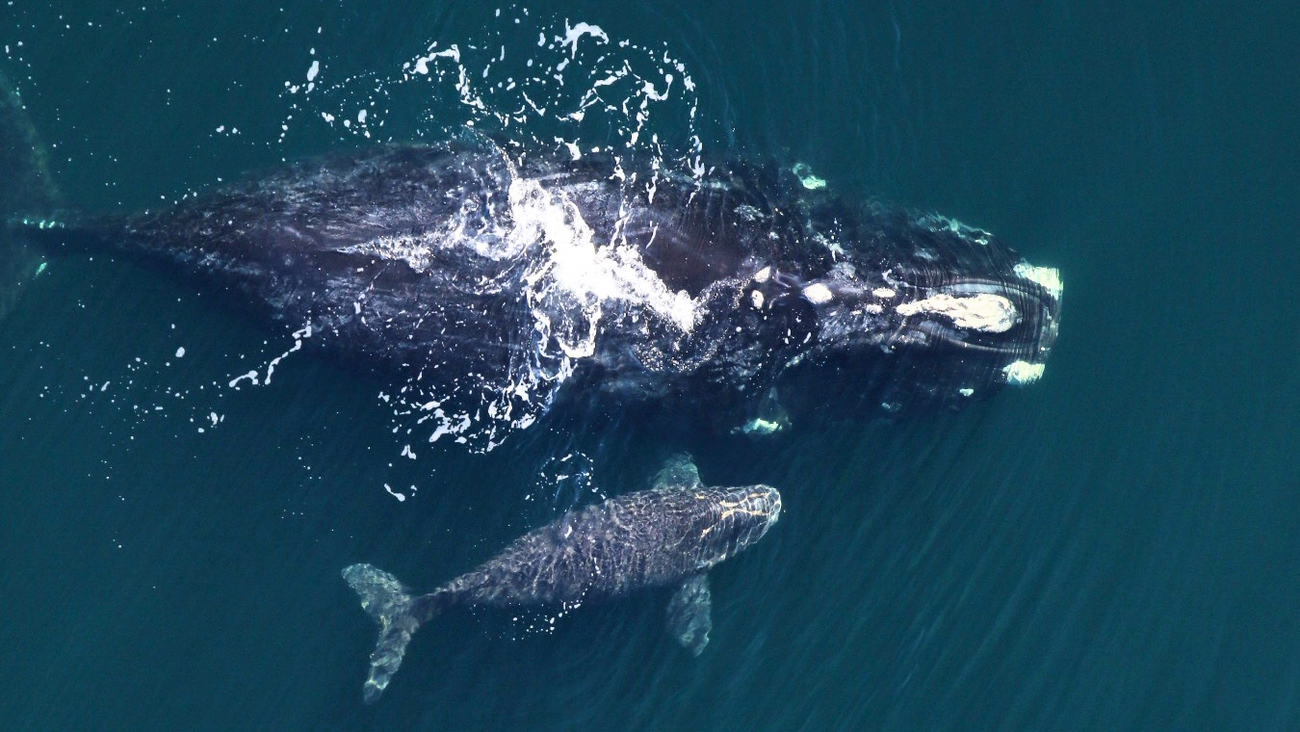

How do mother and calf North Atlantic right whales interact and bond?

Just like many other mammals, right whale mothers and their calves show strong attachments to each other. A calf often shows affection by swimming on its mother’s back. They also butt heads, and a mother may roll over to swim upside down and hold her calf with her flippers. Young whales need to stay with their mother for eight to 17 months and cannot survive on their own at this age.

Despite living in the ocean, whales are mammals and need to drink milk as babies. Some whale species drink more than 150 gallons of milk per day and gain 100 pounds per day in their first few months, consuming 2% to 10% of their body weight in milk every day. Once they’re old enough, North Atlantic right whales feed on copepods (tiny crustaceans) and zooplankton by taking in water and filtering it through their baleen plates.

As you might imagine, drinking milk underwater is a challenging feat. Whales don’t have lips, so the calves can’t suckle like other mammals—instead, they get into position beneath their mothers, who then eject a pressured stream into their mouths.

Right whale mother and calf pairs are especially hard to find because they tend to ‘whisper’ to their calves instead of producing easily recognizable up calls, which can make it harder to acoustically detect them. This is why ‘real-time’ detections cannot be relied upon and why more protections are needed.

Generally, when baby whales are born, they are delivered tail first to prevent drowning, but in some situations, they are born headfirst.

Fittingly, since baby whales are called calves, adult female whales are called cows, and adult male whales are called bulls.

How do researchers monitor North Atlantic right whales?

Researchers track and monitor North Atlantic right whales because their populations are so low and threatened by human activity. Scientists observe them from the air, shore, underwater, or on a boat.

In NOAA’s Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary, an acoustic monitoring network of buoys and gliders equipped with hydrophones helps scientists detect North Atlantic right whales in the Boston Channel. These acoustic data are uploaded to WhaleAlert, a mobile app developed by IFAW, Stellwagen Bank, and Conserve.IO designed to report whale sightings and reduce the risk of vessel strikes.

Today, mariners can also be alerted using automatic identification system (AIS) technology being deployed throughout North Atlantic right whale habitats. Integrated into many GPS systems, AIS delivers safety and navigation messages to all vessels 65 feet and longer, as well as many smaller vessels voluntarily equipped with the technology.

Scientists at IFAW and Stellwagen Bank are looking towards right whale prey to learn more about aggregations of whales. When right whales feed on tiny crustaceans called copepods, they trigger the release of a compound called dimethyl sulfide (DMS) into the water. By analyzing DMS, researchers hope to uncover links to right whale distribution—insights that could support the development of a predictive tool to help implement protective measures before whales arrive in a given area.

Monitoring North Atlantic right whales is no easy task, but through a combination of research, innovation, and observation techniques, we’re gaining critical insights into their migratory patterns—insights that help us better address the risks facing this endangered species.

Can I see North Atlantic right whales?

Whale watching is a great economic alternative to whaling. As long as it is done correctly, it does not endanger North Atlantic right whales. IFAW has worked with communities to develop safe, sustainable whale watching practices, in which the operators and their customers take responsibility and implement measures to protect whales and the ocean.